At 81, architect Stanley Tigerman is a controversial figure, often derided for his blunt criticism of his profession as well as his espousal of postmodern aesthetics. “Ceci n’est pas une rêverie: The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman” presents his 50-plus-year career as a legacy of his battles fought against a Chicago establishment dominated by followers of Mies van der Rohe.

Relying on Tigerman’s drawings and other works on paper—which the architect donated to Yale University, his alma mater—curator Emmanuel Petit assembles a well-organized retrospective. (Its tone, however, is too academic for a man who once designed a house shaped like a penis.)

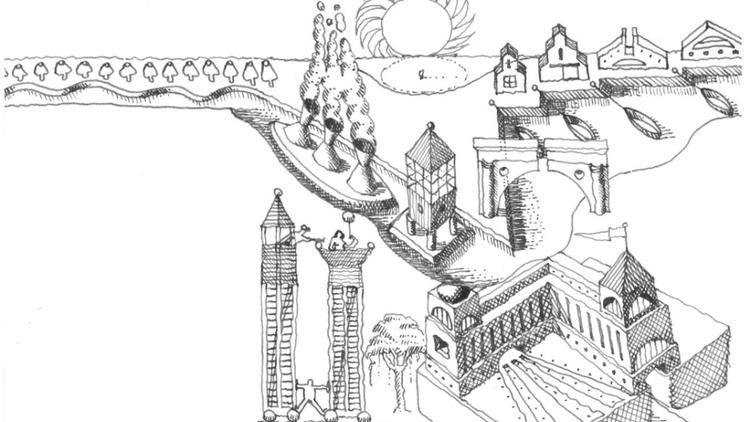

Tigerman’s drawings constantly subvert Miesian ideals: Curves slice through rectilinear geometries; color and whimsy enliven monochrome palettes and “serious” forms. In his satirical photocollage The Titanic (pictured, 1978), the architect sinks Mies’s modernist masterpiece, IIT’s Crown Hall, into Lake Michigan.

Though the exhibition inexplicably omits much of the 1990s, it culminates with Tigerman’s design for the Illinois Holocaust Museum (completed in Skokie in 2009) and other recent works. In the beautiful sketch Graceland Cemetery (1996), Tigerman draws a plan of Chicago centered on Montrose Avenue, with the cemetery, where Louis Sullivan and Mies are buried, at one end and the lakefront—Daniel Burnham’s legacy—at the other. In between lie two of his own built projects, the Pensacola and Boardwalk buildings, as well as what he labels blocks o’ shit.

In this sketch, Tigerman aligns himself with Chicago’s pantheon of great architects and separates his work from the mundane and ubiquitous crap he believes comprises the rest of the urban fabric. In his sardonic way, the architect asks an age-old question: Will history recognize my achievements, or consign me to the trash heap?