The weekend of the NATO summit, I headed for the hills—the Ozark Mountains, that is—and visited the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Founded by Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton, the museum opened in Bentonville, Arkansas, home to Wal-Mart’s headquarters, in November 2011.

According to its mission statement, Crystal Bridges aims “to celebrate the American spirit” through “outstanding works that illuminate our heritage and artistic possibilities.” I feared I would find a PR-fueled fantasy of Wal-Mart as patron of American culture, but the retailer disavows any link to the museum beyond subsidizing its free admission.(The welcoming security guards could be mistaken for greeters, however.)

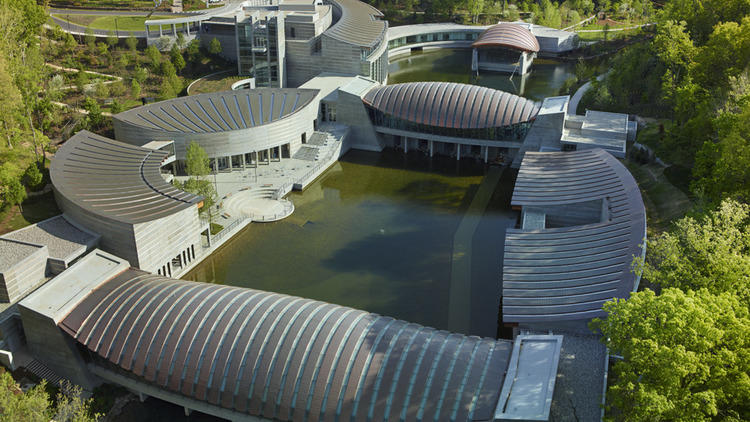

Designed by Moshe Safdie, the museum occupies a series of curvilinear buildings straddling two pools of water created by dams on the Crystal Spring. (The buildings’ ribbed roofs resemble the backs of armadillos, a species found everywhere in the Ozarks.) Safdie constantly connects visitors to the surrounding landscape. I’ve never seen another museum allow one to move so easily between its interior and exterior spaces.

Walton’s collection spans 500 years. The galleries showcasing the 17th–19th centuries contain rare and masterful Colonial-era portraits such as Charles Willson Peale’s George Washington (c. 1780–82) and landscape paintings by the Hudson River School. The finest, Asher B. Durand’s Kindred Spirits (1849), made the heiress notorious when she acquired it in 2005 from the New York Public Library for a reputed $35 million. The Wall Street Journal later described Walton as a “culture vulture, poised to swoop down and seize tasty masterpieces from weak hands,” but she did nothing illegal. The furor reflects a bias against a nouveau riche collector and an assumption that Arkansas is a cultural backwater. Crystal Bridges transcends these prejudices: Though not in a big city, it feels like a world-class museum.

Unfortunately, this impressive institution misses an opportunity to offer an alternative to the white guy’s narrative of American art. Walking through the galleries, I wondered: Where are everyone else’s stories? Except for Robert S. Duncanson, Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker and a handful of Harlem Renaissance artists, few black artists have works on display. Though representations of American Indians abound, all are rendered by white artists. The museum’s traditional vision emphasizes paintings and prints. There are few works of sculpture, no photography, and no folk or outsider art.

Despite several outstanding examples of American modernism, including Isamu Noguchi’s sculpture Lunar Landscape (1943) and Georgia O’Keeffe’s Mask with Golden Apple (1923), the 20th-century collection has many holes. There is little Abstract Expressionism on view, and whole movements and regions are missing, such as the California Color Field painters and the Chicago Imagists.

Crystal Bridges begs the question: What exactly is American art? Women and a few openly gay artists fare better than artists of color, but the wall text says little about their importance. It seems as though the institution’s abundant resources should be used to bring more of these hidden histories to light, so we would have a truer understanding of “the American spirit.”

Still, it was great to see so many locals enjoying the museum. And an American audience can be trusted to question its narrative.