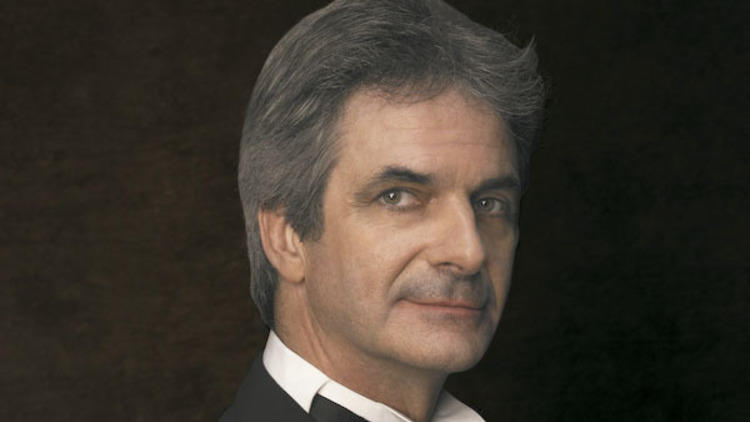

Artistic director of American Ballet Theatre for 20 years, and a star dancer before he accepted the job at age 38, Kevin McKenzie has long been a central figure in classical dance. So when the opportunity arrived to pick his brain—ABT’s first of three biennial engagements at the Auditorium Theatre—I took it. By phone from his New York office, McKenzie calmly elucidated his thoughts on a wide range of subjects.

On Giselle (1841), which ABT performs Thursday 22 through Sunday 25 with the Chicago Sinfonietta:

For all intents and purposes, it’s the same ballet [the world over], the same steps. The sensibility changes over time, as it should.… There are differences in how the music gets put together, in how the first act is constructed to get one to that dramatic, tragic ending that sets up the second act. But in essence, all Giselles tell the same story of the hubris of a man who thinks he can get away with anything, and the innocence of a young girl who believes in fairy tales. When reality crashes down on both of them, it spells out [for the young duke Albrecht], “A life adjustment needs to be made.”

On Albrecht, a role that McKenzie gave “a masterful emotional progression toward an outburst of feeling,” according to The New York Times, and was coached in by two of its greatest interpreters, Mikhail Baryshnikov and Erik Bruhn:

Make a choice: Play him like you’re not necessarily in love with [Giselle], just in love with the idea of being in love and a little bit of dalliance; or take the road that she’s gotten under your skin and you think that you can get away with [an affair while engaged to the prince’s daughter, Bathilde]. Otherwise, you’re just ambiguous, and there is no tragedy because you deserve your fate. [Switches to a cocky, overconfident voice] “Hey, I’m the dude. I’m royalty. I’m bored with court life and here’s this delightful girl, my God, who’s just fabulous, and I can lead this double life because I am who I am. Who’s gonna stop me? I’m clever. I’ll cover my tracks.” [Albrecht’s] is a sin of hubris, no matter how sincere or insincere he may be.

How differently do the five men scheduled to perform Albrecht in Chicago interpret this man?

As far as what the classicism of a nobleman pretending to be a peasant looks like, you get a wide range of interpretations, based on their sensibilities. It’s very individual, even though they’re all dancing the same steps and even mostly the same phrasings. It’s like in Hamlet, that line, “To be, or not to be?” There’s a huge range of ways you can lead up to that line and then say it.

On the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at ABT, founded in 2004:

What I did not want was a school that had a style attached to it. I’m of the belief that style [in ballet] is like our clothes: We put them on and we take them off. You feel and act differently in a pair of jeans than you do in a tuxedo. [Graduates] need to show the difference between Vaganova and Bournonville and Balanchine, even though it’s all tendus and jetés. So that’s what led to the development of our National Training Curriculum. That think tank is the philosophy of the school and it’s working well. It’s beginning to produce students that have good choreographers’ tools, who know how to focus and concentrate, how to learn and make adjustments quickly.… The Healthy Dancer part of that curriculum is a network of health professionals, of sports medicine and dance medicine professionals and child psychology development specialists [who help us answer the questions], What’s age-appropriate work? How do you spot problems? What resources do you provide?

On moving ballet training forward:

I think the world of [Switches to a heavy Russian accent] “You too fat. You never dance. Get out. Do now.” Those days are gone.

They’re gone? Really?

Oh, I don’t know that they’re gone, but they should be. We’re leaders, and so we need to set the example.

On the purpose of studying ballet:

Whether [a JKO student] ends up being a professional dancer or not, we want them to have an excellent experience with the art form that they can take forward for the rest of their lives. You send your kids to school and expect them to read Shakespeare. You don’t necessarily expect them to become Shakespearean actors. If they do, great, but what you hope they learn is what his plays have to say about, number one, art, and number two, life. And that’s what ballet should be.

On his goals for the future of ABT:

To become a creative laboratory. We’ve defined ourselves as the national company, which means we mount the great, big, full-length classics. So the next step is, What’s the new classic?

What do you think it is?

I think it lies in [artist-in-residence Alexei] Ratmansky’s brain. And I’m pickin’.

How far into the future does that relationship extend?

Another 10 years, for now. Far enough out that we’re hoping for, at the very least, one more original full-length ballet [choreographed by Ratmansky].

On the evolution of artistic directorship:

There isn’t a new normal yet. All of the rules have changed, [Laughs] because we, as a society, lived the lie that we could get something for nothing. It’s demanded now that nonprofits [be] smartly run businesses. In the past, an artistic director said, “This is good. We must do it. Find the money. Shut up.” And people did.… I don’t get to be the guy who stamps his foot and says [that]. I have to go, “Let’s not give up on this idea. How do we make a plan for it?” You get the money in place before the plan, or you alter the plan. Ultimately, it’s just the real world inserting itself into our profession. You can’t just spend money because something is a good idea. You have to justify it.

On the relationship between boards of directors, company managers and artistic staff:

The relationship between boards and managers is different these days but the dynamic of business versus art has never really changed. An artist is always in need of a patron and a patron never likes being taken advantage of. That’s the simple truth.

You recently exercised a non-competition clause with regard to Natalia Osipova and Ivan Vasiliev, dancers who perform both with ABT and with the Mikhailovsky Ballet in Russia. Are there times when that clause has been waived in the past and, if so, what factors into whether or not you enforce the terms of agreements concerning international stars?

[ABT] has excercised that clause a lot and it’s waived it a lot, on a case-by-case basis. I view it on this level: There’s a professional courtesy that performers and managers within the same organization give each other. If you’re scheduled to perform with your home company, you don’t perform three months before or after [with another company] within a 100-mile radius without giving notice. [If you would like to do that], bring it up and we’ll talk it out. With any of ABT’s principals, the expectation is set that I won’t release them while we’re in the Met because, number one, [the Met season] is so dense: 64 straight performances. For [principal dancers] to be getting on planes, going somewhere [to guest] and coming back, is wear and tear that—they can do that later in the year, unless it’s an extraordinary opportunity. We do make adjustments for what they want to do but, you know, a dancer wants to do everything all the time. They don’t need to do everything all at once, all the time. That’s my role, to keep the needs and wants lists clear.

The “star system” and international guesting comes and goes in the ballet world. It’s certainly common right now but hasn’t always been in the past. Is engaging principals from other countries always a win? Do you prefer the current system any more or less than a paradigm where dancers are firmly associated with single companies?

It is the paradigm right now [to engage guest artists]. But I’d like to be really clear: Yes, I engage guest principals, but my own principals are guests everywhere else. I’m not only juggling bringing people in; we’re juggling our own people’s schedules, too. [ABT dancers] have the right to go out and be guests. It’s a good thing for people to cross-pollinate.

So if someone wants to be catty and say that ABT stands for “Ardani Ballet Theatre”…

[Laughs] Yes, I would say that’s what that sounds like.

Because it’s only half true.

Exactly. Now, there was a moment in time when you might’ve called us South American Ballet Theatre… [Laughs]

Do you and Sergei Danilian of Ardani Artists, the agency that represents Osipova, Vasiliev and other ballet stars, work directly with one another?

Oh, yeah! All the time.

American Ballet Theatre employed about 100 dancers in the ’80s, was at 67 members when you became artistic director, and now counts about 90 members including guests. What would you say is the best size for a classical company like ABT?

The disadvantage of not having enough people is that you can’t maintain quality. No matter how many you have, you don’t have use of 10 percent of them on any given day. They get injured, they get sick, whatever. They’re human. There’s a threshold below which we cannot go and be able to produce consistent quality. The tricky balance is to provide upward mobility and also help [dancers] understand that they have to maintain their stations, if you will. We have a system of casting that builds in covers. Every single role, every single person on that stage, is triple-cast. There’s always another person who can go in, if someone gets hurt, or we can move the puzzle pieces around. Which allows me to give corps members soloist roles, and give soloists principal roles. There’s that flexibility within the company to develop people. When a company’s smaller, it forces you to lock people in: “You’re doing corps parts this year, that’s it, sorry, I can’t give you another opportunity because I don’t have another person to replace you in the spot I’d be taking you out of.”

How do you feel about the company’s current size?

We’re just short of what we really need, by between two and five dancers. We’re always scrambling. That’s a budgetary issue. But we’re close.

Professional dancers’ careers are short, and yet choreography evolves quickly. Are there any roles created since you’ve retired that you would’ve liked to perform? Any choreographers today whose movement appeals to your dancer self?

What an interesting question. I haven’t thought of it in terms of, “Ooh, I’d like to get up onstage and do that!” But I’ve seen things—there are parts of [Ratmansky’s] The Bright Stream where you just go, “Oh, my God,” that are sensational. As a performer, I loved to partner. When I see some of these fantastic things that [James] Kudelka used to do and what [Christopher] Wheeldon and Ratmansky are doing, how they have dancers interact in such inventive ways, that are so, so clever, that’s when I think, “Boy, that must really be fun to do.”