I woke up on the jail floor around 8am to what sounded like a prison riot.

Thunderous pounding and shouts of “Pigs!” echoed through the drab, concrete hallways of the 1st District Central at 17th and State Streets. I shot up. “There’s a woman,” my cellmate explained, “that needs her [heart] medicine, but the officers won’t come to her cell.”

For a drowsy moment I couldn’t figure it out: How did I end up here? In my 23 years, I’d never been in trouble with the law. Then it all came back. Just before 1am on October 23, I was among 130 Occupy Chicago protesters arrested in Grant Park near “The Horse,” the movement’s nickname for the park area around the pair of bronze equestrian statues The Bowman and The Spearman.

I remembered it all. How the police bullhorn reverberated, carrying a warning: “Vacate the premises, or you will be arrested!” How reporters from The Wall Street Journal to Al Jazeera circled the camp trying to find one last interview. And how a police officer lifted me from the ground, tightly zip-tied my hands behind my back and led me to the waiting police van. Inside, some of my comrades managed with their bound hands to pull out their cell phones to tweet, text and Facebook—fitting for a movement driven by social networking.

At the station, we were put into a holding cell and, one by one, processed. I posed for my mug shot and placed my hand to a glass scanner plate for the electronic fingerprinting. An officer gave me a receipt for the things they confiscated—a belt, tie, scarf, my wallet, phone, audio recorder, $10.45, and my Occupychi.org armband—and led me to the cold nine-by-seven-foot cell that would be my home for 11 hours.

My cellmate, Jonathan, was a vegetarian, but when an officer offered bologna sandwiches, we both accepted. Following that pitiful dinner, I caught the attention of another officer and asked for my one phone call.

“Nope,” he said, chewing on the inside of his lip.

“What do you mean?” I was baffled that prison movies could’ve led me astray.

“Done missed your chance,” he said. “You’re supposed to do it while being processed.”

A lucky man who was finally allowed to make a call shared information from a rep with the National Lawyers Guild who said the police would probably release us starting at noon; however, they could legally hold us for up to 48 hours.

From various cells, demands for toilet paper were made for hours, until an officer begrudgingly doled out a single roll. To share a square, people rolled it across the hall.

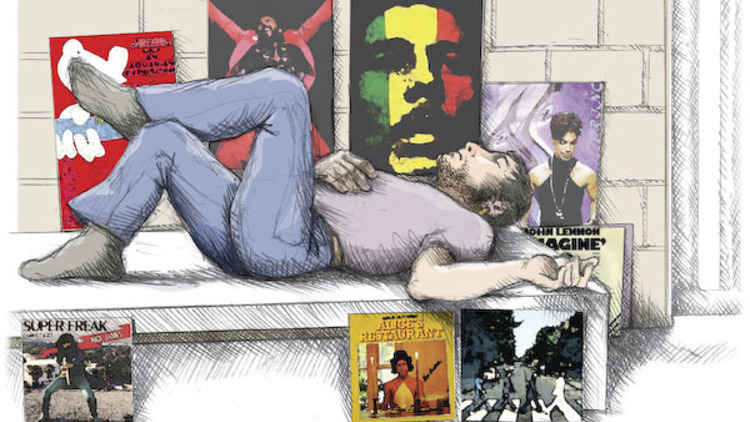

After flushing our in-cell toilet, I made a bizarre discovery. In a plastic bag hidden behind our commode were about five-dozen vinyl records: Rick James, Marvin Gaye, Prince, Bob Marley. We decorated the cell with the few pullout posters, lined the cold concrete benches with the sleeves and then tried to share our bounty. The records made their way down the block of imprisoned protesters, slid across the hallway from cell to cell.

At 12:30pm, we were finally let out into the warmth of a sunny Sunday afternoon. Around 50 people from Occupy Chicago greeted us with coffee, doughnuts and bagels. A handful of news cameras captured the reunion.

I signed up for a lawyer with the NLG, which offers highly affordable legal services, and walked away from the jail with my $120 I-bond, a court date (Wednesday 16)—and an even more tenacious dedication to the Occupy movement. After a much-needed nap, I was back in front of the Chicago Federal Reserve.